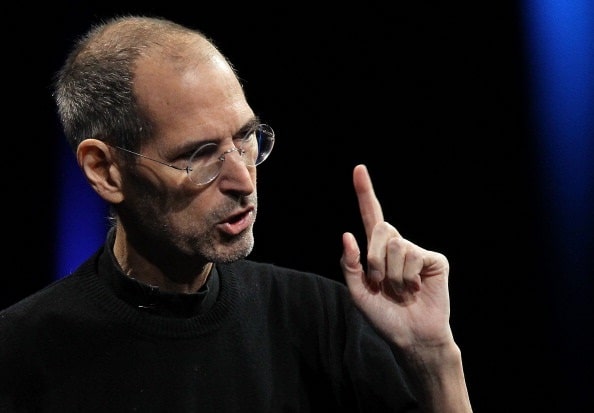

Steve Jobs was the man who halted one media sector’s slide in to oblivion. Bringing others to a 21st Century cast in his likeness is a project that goes on.

Apple’s greatest creations may be its simple, sexy hardware, but Jobs’ greatest impact was marrying that hardware with the iTunes Store. Here, his greatest legacy is convincing users of a Wild West internet, reared on a mantra of “information wants to be free” and a growing pirate culture, to pay for new digital content like they used to offline.

Against games, sports, video and news, music is the only digital content type with an audience of customers willing to pay at consistently healthy growth rates, according to Forrester research. That is the iTunes effect. Though many around still fret over whether “paid content” can work, many forget that this economy already has come to pass – and there is one figure above all who made it happen.

Before Jobs’ intervention, record labels had looked on as sales of plastic music declined and as Napster, Limewire and Gnutella ruled the waves and mobile app developers struggled to gain scale in the absence of viable, legal commercial alternatives. Even the rebirth of the Walkman as music players like iPod, on to which users could transfer ripped-off songs, might have contributed to the worry. But allying a music store with the device was a master stroke that no one else had pulled off until Apple.

“Until Jobs persuaded the music labels to try selling songs individually for 99 cents, no one had found a formula for selling music online to compete with the illegal file-sharing networks,” writes Leander Kahney in his book Inside Steve’s Brain. “Since then, the iTunes music store has become the Dell of digital music.”

To be sure, record labels have not been returned to absolute rude health. By revenue, industry sales are still declining. But, without iTunes’ intervention (and the takedown of Napster et al in courts), the music business might have been truly killed off by now. What’s more, by volume, single music sales have never been healthier.

Where Apple’s gadgets bear designer Jonathan Ive’s fingerprints, iTunes carries Jobs’ imprimatur: it allowed Apple (NSDQ: AAPL) to become a post-PC company and allowed Jobs to mingle, wheel and deal with the gatekeepers of the entertainment industry. “Jobs prefers to negotiate one-on-one and let lawyers tie up the details after the handshake is done,” according to a 2006 BusinessWeek profile. (Jobs already had a hand in the movie business through animation studio Pixar, later sold to Disney.)

“I have met Steve Jobs and even done a deal with him face to face in his kitchen in Palo Alto in 2004,” U2’s manager Paul McGuinness once told an audience at the Midem music conference. “No one there but Steve, Bono, (Interscope’s) Jimmy Iovine and me, and (Universal Records’) Lucian Grainge was on the phone.

“We made the deal for the U2 iPod and wrote it down in the back of my diary. We approved the use of the music in TV commercials for iTunes and the iPod and in return got a royalty on the hardware. Those were the days when iTunes was being talked about as penicillin for the recorded music industry.”

The iTunes Store may have succeeded because it replicated familiar old modes of retail – selling individual units of content at distinct price points through a big store – rather than re-inventing the wheel in to a shape that record and other media bosses might not recognize (it is only in 2011 that the more radical “celestial jukebox” of unlimited consumption is gaining hold). “Genius” Steve Jobs may be called; in many ways, “centrist” might be equally applicable.

But, though Jobs’ iTunes may have been a bulwark to the deadpool for media executives, content has also only ever been the carrot to Apple’s stick – selling highly-priced, lust-worthy gadgets – and Apple’s dominance of the music retail market a source of consternation. Music bosses lately have embraced services that might diminish iTunes’ share.

Though its name still bears the same musical heritage on which it was founded, iTunes store would become Jobs’ multi-media project – a superstore for TV, movies, podcasts and, lately, books, newspapers and magazines. Even the Starbucks “pick of the week” includes apps and books, in addition to music.

A mix of issues around pricing, control and fragmentation, kept Apple from replicating its musical success in any of these areas but the model is still the standard — and Jobs is the innovator who helped content industries reimagine themselves digitally in their traditional analog image.

More on Steve Jobs in our archives.